Once upon a time, last fall, while settling back into teaching after a spring sabbatical, I found myself diving into social media. I was already there in many ways, of course. I have a twitter account. I have this blog. I have other sites, old and sundry, for non-academic diversions. But I had let much of that go during my sabbatical as I buried myself in reading documents from the late Qing dynasty (1644-1911). Indeed, I avoided the internet and focused instead on readings in classical Chinese, particularly the bureaucratic missives composed by officials of a sputtering dynasty at the end of the 19th century. It was an analog endeavor, save for note-taking in the blessed Scrivener program.

Once upon a time, last fall, while settling back into teaching after a spring sabbatical, I found myself diving into social media. I was already there in many ways, of course. I have a twitter account. I have this blog. I have other sites, old and sundry, for non-academic diversions. But I had let much of that go during my sabbatical as I buried myself in reading documents from the late Qing dynasty (1644-1911). Indeed, I avoided the internet and focused instead on readings in classical Chinese, particularly the bureaucratic missives composed by officials of a sputtering dynasty at the end of the 19th century. It was an analog endeavor, save for note-taking in the blessed Scrivener program.

In the fall, though, I was back to social media full-time and thinking of other ways to use it. For years, I’ve been exchanging emails with a few close colleagues in the China field, sharing links to all sorts of interesting things: online resources for research and teaching, as well as news stories and commentary from a broad variety of sites in multiple languages, video, maps, and images. And I thought: wouldn’t it be great to have a site at which to share this stuff, to get beyond email, and have it available for my students, and perhaps beyond?

I should note that I do tweet much of this stuff, too, but somehow 140 characters doesn’t always seem to do the material justice. I understand, of course, that’s also not quite the point of Twitter, which is wonderful as a speedy, collective resource for sharing links and quick communication. It’s just that I’ve been looking for something with a bit more — what is it? elasticity, perhaps, when it comes to composition.

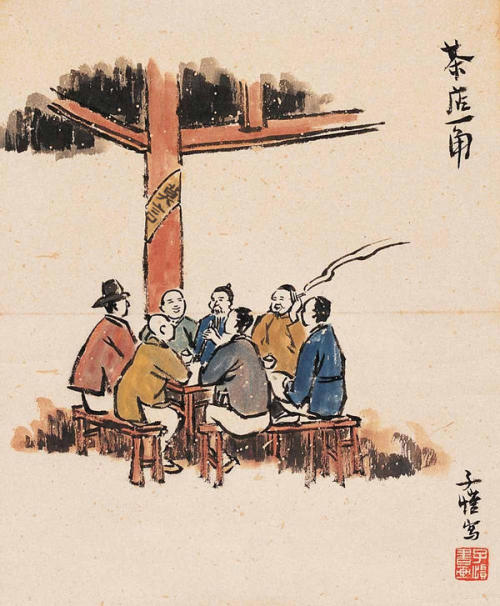

Enter Tumblr, a frame I’d fiddled with previously and all but forgotten. More flexible than Twitter, and quicker than WordPress (my other favorite frame for web composition.) Returning from sabbatical, I hopped in and set up a new site there. I chose the name “Gulou” 鼓樓, the Chinese word for “Drum Tower.” Reasons for the name? Perhaps the invocation of “drum” reminded me of a news site, almost as some kind of herald. More immediately, it’s a reference to a historic site and neighborhood in Beijing itself (a neighborhood, like many historic sites in the city, that’s currently being torn down.) And, side-note, I also have fond memories of sitting outside on the rooftop balcony of a friend’s apartment in that same historic “Gulou” neighborhood one hot summer evening in 2000, engaged in excellent conversation with a crowd of China specialists (while drinking a very, very good martini.) That may be the true inspiration for the name.

And it all seems to fit with the spirit of the site. I’m now closing in on my 400th post. It’s a page at which I, as editor, share links to news stories and blog posts related to China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, and beyond. I also share online resources for teaching, translated works, video, archival sites, and news of interesting museum exhibits or public talks.

Key themes? Politics, society, the environment, new media, and more. My emphasis is on the local and the global, the latest news and valuable resources related to understanding East Asia region and its central role in global affairs for the 21st century.

It’s been interesting to watch the audience build over these past eight months. The majority of my contacts on Twitter are my age or beyond, i.e. mid-career professionals. In keeping with Tumblr’s own demographic, meanwhile, I’d say my audience is a mix of youth (including many high school students) as well as college students and young professionals, entrepreneurs, artists, non-profit and NGO associates, and the like. While there’s some overlap with my Twitter audience, I’d say the demographic is rather different. And that seems quite valuable.

Just a week ago, meanwhile, I received two bits of very good news for the site. One was that I had one of my posts featured for the first time by Tumblr editors. The post shared a recent story of Hong Kong’s highest court ruling in favor of allowing a transgender woman to marry, a ruling that was a major event both in Hong Kong and globally.

At the same time, I also received an invitation to have Gulou featured on Tumbr’s spotlight page for news services. It’s now introduced there alongside established media (Reuters, LA Times, CNN, USA Today, etc.) and also accompanies other, less traditional but equally popular sites for news consumption (e.g. The Daily Show) on the same page.

I’m just beginning to ponder the implications. What does it mean that an individual’s site—one person’s own, simple Tumblr—is beside the site of a news agency like, say, Reuters, a major news organization founded in 1851 (and now owned by The Thompson Corporation)? More immediately, at least for a scholar of China and Asian Studies, what does it mean that a microblogging, pop media site such as Tumblr is interested in featuring stories from that region at its top-most news page?

On a more practical note, I’m also wondering what it means that another corporation, Yahoo, has just bought Tumblr for, apparently, $1.1 billion cash. For now, it’s a reminder that I have to get going on the plan to back up my Gulou content at Tumblr to my own domain. While the Gulou conversation (with or without martinis) will continue, I’m sure, I find myself less and less apt to trust other online venues (hello, Google Reader…). So I’ll be trying to catch up on my own project reclaim here (many thanks to Jim Groom for advice on this score) while contemplating the deeper implications of the intersections of new media, scholarship, and global/public audiences.

*Title reference, yes, to Philip Levine’s “Drum” — “Leo’s Tool and Die, 1950” poem.

Sorry I am so late to this party, but this may be the single most important moment for UMW and social media, why aren’t they bouncing off the walls. Like so many events with the web over the last decade, such an incident helps redefine the idea of public scholarship in the digital world. I sometimes lose patience with the whole digital humanities movement and discussions because they seem to miss the fact that it isn’t so much about creating a new discipline as it is about incorporating the possibilities of the digital into the current one. The ability for you and your colleagues in Chinese History to share your resources publicly is that revolution, and it is beautifully simple in its power to shift access and reach.